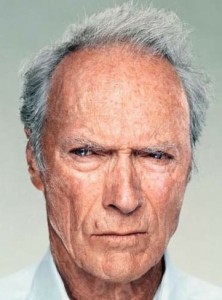

Good, bad, ugly, and the empty chair too, I love arguing Eastwood

Every few days this realization makes me pause, as if I’d been struck with Déjà vu or forgotten my keys somewhere. As a lifelong Eastwood enthusiast (having winced my way through some of his ‘80s choices only to beam with pride when he came to his senses), I dread his absence – and also his last laugh at leaving us to ourselves.

Every few days this realization makes me pause, as if I’d been struck with Déjà vu or forgotten my keys somewhere. As a lifelong Eastwood enthusiast (having winced my way through some of his ‘80s choices only to beam with pride when he came to his senses), I dread his absence – and also his last laugh at leaving us to ourselves.

Will I know what to do with myself when that day comes? Yeah. But I’ve never lived in a world without with Clint Eastwood – have you?

Every now and then some Eastwood reminder will come my way or I’ll exit my house past a huge The Good, The Bad and The Ugly poster that hangs by our front door. Not enough space here to list all the reasons I admire the man, but the three that most frequently come to mind are his elderly grace, professionalism, and class. You see, I love ‘im for what he is now because it makes what he was then so much cooler.

Reader note: GUILTY PLEASURES – I’ll be recapping familiar biographical tidbits here as well as geekin’ out on Dirty Harry, so if you dislike Eastwood or don’t care for the re-run, know your limitations.

I was 10 years old in ‘77, when Eastwood starred in The Gauntlet. I remember trying to talk one of my uncles into taking me to see it, waving around the newspaper ad and promising that an entire city bus would get filled with lead by and a thousand cops. I overheard sticks-in-the-mud dismiss it as trash, declaring that it had no plot, filthy language, and “guns for no reason.” Can you imagine? Guns for no reason? Only adults think like that. Guns are the reason! I even swore to my uncles there’d be no disappointment because it wasn’t a Dirty Harry movie, knowing that all you had to do was pretend Harry Callahan had moved to Arizona. I’ve been picking apart that curse-strewn bullet-fest ever since, and I need to see it right now.

1978’s Every Which Way but Loose finally stopped me from trying to stretch every Eastwood movie over Harry Callahan’s form. A lot of people hated that movie, but I was young and enamored enough with Eastwood to enjoy every minute of it. (Face punching for no reason? Face punching is the reason!) Besides, I’m sure Inspector Callahan would’ve have dragged that Orangutan around for as long as it continued to piss off Lt. Briggs.

1978’s Every Which Way but Loose finally stopped me from trying to stretch every Eastwood movie over Harry Callahan’s form. A lot of people hated that movie, but I was young and enamored enough with Eastwood to enjoy every minute of it. (Face punching for no reason? Face punching is the reason!) Besides, I’m sure Inspector Callahan would’ve have dragged that Orangutan around for as long as it continued to piss off Lt. Briggs.

Escape from Alcatraz didn’t have shootouts, but it had Eastwood’s indignant gloominess and more face punching. Just before it came out my dad and I were unloading a cart at the grocery store when I caught the man’s glower among the tabloids (he was on the cover of the July ’79 issue of LOOK magazine). My father’s refusal to let me place it on the hallowed conveyor forced me to read quickly. As of that issue’s publication, read the article’s subtitle, Clint Eastwood was 49 years old and the age-watch had begun. For me, everything Eastwood became that much more important, especially repeating his snappy lines in the right voice and finding something to love in every single movie he made. First stop: subtlety, which Escape from Alcatraz had a lot of compared with, say, collapsing an entire house with only bullets.

Escape from Alcatraz didn’t have shootouts, but it had Eastwood’s indignant gloominess and more face punching. Just before it came out my dad and I were unloading a cart at the grocery store when I caught the man’s glower among the tabloids (he was on the cover of the July ’79 issue of LOOK magazine). My father’s refusal to let me place it on the hallowed conveyor forced me to read quickly. As of that issue’s publication, read the article’s subtitle, Clint Eastwood was 49 years old and the age-watch had begun. For me, everything Eastwood became that much more important, especially repeating his snappy lines in the right voice and finding something to love in every single movie he made. First stop: subtlety, which Escape from Alcatraz had a lot of compared with, say, collapsing an entire house with only bullets.

John Wayne died a week after that movie’s release, and I recall arguments galore over who was better, Wayne or Eastwood. Thirty-two years later I don’t hear anyone comparing Eastwood to today’s movie tough-guys or leading men – as if you could actually make such a comparison with a straight face – but back then it was people griping about “these kids today” and insisting the world was a better place when John Wayne and Elvis ruled it. In contrast to their public personas, nailed as they were to the patriotic white establishment, Eastwood stuck around by adapting his character choices to his age. It’s a smart lesson.

John Wayne died a week after that movie’s release, and I recall arguments galore over who was better, Wayne or Eastwood. Thirty-two years later I don’t hear anyone comparing Eastwood to today’s movie tough-guys or leading men – as if you could actually make such a comparison with a straight face – but back then it was people griping about “these kids today” and insisting the world was a better place when John Wayne and Elvis ruled it. In contrast to their public personas, nailed as they were to the patriotic white establishment, Eastwood stuck around by adapting his character choices to his age. It’s a smart lesson.

Besides, I can’t imagine Josey Wales forfeiting the time or brainpower to badmouth teens who don’t know better. I’m sure Dirty Harry would, but only if the kids were carrying bazookas. And Walt Kowalski definitely would, but his myopia was also the vehicle used to teach his audience the lessons of Gran Torino. The point is, Clint Eastwood (the actor) infused his characters with a strong suspicion for the establishment and the reasoning behind its customs, beliefs, and hypocrisies.

Besides, I can’t imagine Josey Wales forfeiting the time or brainpower to badmouth teens who don’t know better. I’m sure Dirty Harry would, but only if the kids were carrying bazookas. And Walt Kowalski definitely would, but his myopia was also the vehicle used to teach his audience the lessons of Gran Torino. The point is, Clint Eastwood (the actor) infused his characters with a strong suspicion for the establishment and the reasoning behind its customs, beliefs, and hypocrisies.

To be fair, more than a few of John Wayne’s characters also possessed those qualities, but they were unambiguous men – very Old Testament. By the end of his career he was as stiff as the bronze sculptures of him that now stand in (a-hem) Beverly Hills and Orange County. If the Duke had his moments, he also had his baggage.

At first, while Eastwood’s career was taking off, he too was lumped in with the establishment: cowboy hats and tumbleweeds were the very definition of mainstream regardless of whether Sergio Leone was simultaneously redefining the western genre. Soon after becoming a bigger star than even Rawhide had made him, various critics and counterculture types went so far as to declare Eastwood’s Dirty Harry character a right-wing symbol of tyranny and hippie-bashing. I say they didn’t get it. There was something different – or perhaps indifferent – about Dirty Harry. Sure he was a cop, but he was a cop who talked like a beatnik, loathed the officeholders who made the rules, and essentially questioned the establishment’s order. His disregard for safety and procedure was impossibly flagrant. Dirty Harry was the kind of the cop who would’ve regarded Adam-12, the most popular TV show of the era, as conformist horseshit.

At first, while Eastwood’s career was taking off, he too was lumped in with the establishment: cowboy hats and tumbleweeds were the very definition of mainstream regardless of whether Sergio Leone was simultaneously redefining the western genre. Soon after becoming a bigger star than even Rawhide had made him, various critics and counterculture types went so far as to declare Eastwood’s Dirty Harry character a right-wing symbol of tyranny and hippie-bashing. I say they didn’t get it. There was something different – or perhaps indifferent – about Dirty Harry. Sure he was a cop, but he was a cop who talked like a beatnik, loathed the officeholders who made the rules, and essentially questioned the establishment’s order. His disregard for safety and procedure was impossibly flagrant. Dirty Harry was the kind of the cop who would’ve regarded Adam-12, the most popular TV show of the era, as conformist horseshit.

As Eastwood allowed his subsequent characters to straddle the line between awful and anti-hero, his audiences were free to seek out the good in them (or argue about it later). At the very least, Clint Eastwood’s younger audiences knew they wouldn’t be as blatantly patronized by his characters as they were by others of the era, which went a long way in the 1970s.

It sure went a long way with me! By the time Escape from Alcatraz came out my friend Chuck and I had memorized all the best Callahan-isms, from “You gotta ask yourself, do I feel lucky?” to “When a naked man is chasing a woman through an alley with a butcher knife and a hard on, I figure he isn’t out collecting for the Red Cross.” I was sent home from school when I repeated that last one to a nun, but fortunately Eastwood was juuuust “establishment” enough not to get sent out of our house as well.

It sure went a long way with me! By the time Escape from Alcatraz came out my friend Chuck and I had memorized all the best Callahan-isms, from “You gotta ask yourself, do I feel lucky?” to “When a naked man is chasing a woman through an alley with a butcher knife and a hard on, I figure he isn’t out collecting for the Red Cross.” I was sent home from school when I repeated that last one to a nun, but fortunately Eastwood was juuuust “establishment” enough not to get sent out of our house as well.

As the ‘80s progressed it became interesting to watch how the Eastwood “filter” somehow scrubbed off part of the lameness of traditional Hollywood tropes. Don’t get me wrong, there’s never been anything independent or alternative about Clint Eastwood “the brand;” he’s always been part of the easy-culture mainstream machine. Yet there’s that slight distortion he brings to his characters that somehow makes even his campy choices more interesting. Obviously most of the movies he made during that decade couldn’t hold a candle to Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, The Gauntlet, or The Eiger Sanction: we got Firefox, City Heat and the unsatisfying end of Inspector Callahan in The Dead Pool (that is, if you fail to pretend that Gran Torino’s Walt Kowalski is actually Dirty Harry at the end of his life). But even duds like Pink Cadillac were made forgivable by Unforgiven, arguably the best western ever made. I’ve got similar praise for his 2003 screen adaptation of the psychologically complex Mystic River.

With the release of Million Dollar Baby in 2004 Eastwood again gave us face punching, but for a very good reason: to examine the subject of euthanasia. For that the National Spinal Cord Injury Association and other advocacy orgs claimed he had a “vendetta” against the disabled. Eastwood went from “trash” and “filthy” and “guns for no reason” to “misleading“ and “pitch-dark substance.” I just loved that he continued to be Clint Eastwood, always a click or two off the beaten path and using his voice to challenge conventional comfort zones.

By 2006 Eastwood was still “mainstream uppity.” The manner in which he directed his WWII meat grinder, Flags of our Fathers, placed the deepest skepticisms of a soldier’s purpose and duty not on the shoulders of a courageous hero like John Wayne but on a shamelessly exploited Native American – a hope-to-die alcoholic (Adam Beach). And if that wasn’t enough, in the same year he used an adaptation of Red Sun, Black Sand, to co-produce and direct a companion film, Letters from Iwo Jima, to depict the same battle from the perspective of the Japanese enemy.

By 2006 Eastwood was still “mainstream uppity.” The manner in which he directed his WWII meat grinder, Flags of our Fathers, placed the deepest skepticisms of a soldier’s purpose and duty not on the shoulders of a courageous hero like John Wayne but on a shamelessly exploited Native American – a hope-to-die alcoholic (Adam Beach). And if that wasn’t enough, in the same year he used an adaptation of Red Sun, Black Sand, to co-produce and direct a companion film, Letters from Iwo Jima, to depict the same battle from the perspective of the Japanese enemy.

If you enjoy all things Eastwood as much as I do, these biographical tidbits are nothing new. So gettin’ back to a World Without Eastwood: who’s got balls enough to make a movie about the Battle of Falluja from the perspective of the Taliban? Pitt? Gosling? McG? I think not.

Eastwood’s “controversial” 2012 Super Bowl halftime Chrysler ad got me wondering who could possibly replace the man. Who’s gonna keep it together ‘til the very end as he has and still go out droppin’ the raspy voiced one-liners that only he can deliver?

“Get off my lawn…”

“I’ll kick you so hard, you’ll be wearing your ass for a hat.”

“It’s Halftime in America…”

and so on…

Clint Eastwood is gonna die soon. And I guess it doesn’t matter who winds up being compared to his legacy in the future, so long as they’re smart enough to evolve and smart enough not to smoke their way into cancer-ridden lungs. Whoever it is will have to take age-appropriate roles, not take the media seriously, and remember that you can’t become your own country unless you play with the politics. And, finally, he’ll have to be smart enough not to make excuses for trying to be all things to all people. Career longevity and class don’t allow it.

Clint Eastwood is gonna die soon. And I guess it doesn’t matter who winds up being compared to his legacy in the future, so long as they’re smart enough to evolve and smart enough not to smoke their way into cancer-ridden lungs. Whoever it is will have to take age-appropriate roles, not take the media seriously, and remember that you can’t become your own country unless you play with the politics. And, finally, he’ll have to be smart enough not to make excuses for trying to be all things to all people. Career longevity and class don’t allow it.

Much appreciation to Eff Yeah Clint Eastwood