Anti-loitering architecture forces the homeless out into the shame

Kristin Hohenadel’s Slate.com piece on “managing” London’s homeless (“Are Anti-Homeless Sidewalk Spikes Immoral?”) points to a Change.org petition that insists we give a damn about vulnerable populations rather than ostracize them with defensive architecture. The “spikes” that sparked the outrage>petition>renewed UK debate>this blog entry were installed near the entrance of a luxury residential building in London on June 10, 2014.

Kristin Hohenadel’s Slate.com piece on “managing” London’s homeless (“Are Anti-Homeless Sidewalk Spikes Immoral?”) points to a Change.org petition that insists we give a damn about vulnerable populations rather than ostracize them with defensive architecture. The “spikes” that sparked the outrage>petition>renewed UK debate>this blog entry were installed near the entrance of a luxury residential building in London on June 10, 2014.

The article’s example pictures of “anti-bum” devices, culled from artist Nils Norman’s international collection, show a callousness that is not, to me, the least bit surprising. For years, I’ve referred to nasty urban planning designs like these as “MAN-EATERS” since they frequently resemble shark teeth. Here in Los Angeles, in a world of caged trash bins and spatial confinement of the homeless, we have a disheartening array of them.

We’re not alone, though: across modern urban landscapes everywhere, commercial and residential developers are planning and designing “exclusionary” access ways and loading docks to discourage the poor from setting up shop in doorways and “gap sites,” those architectural nooks and crannies that most of us sinners have been grateful to find at one time or another – usually when drunk. But let’s face it: in every one of us lurks a little NIMBY contradiction, the sentiment otherwise known as, “not in my backyard.”

We’re not alone, though: across modern urban landscapes everywhere, commercial and residential developers are planning and designing “exclusionary” access ways and loading docks to discourage the poor from setting up shop in doorways and “gap sites,” those architectural nooks and crannies that most of us sinners have been grateful to find at one time or another – usually when drunk. But let’s face it: in every one of us lurks a little NIMBY contradiction, the sentiment otherwise known as, “not in my backyard.”

Partiers are grateful to find a place to pee, sure, but don’t want to work near or pass through one of these stink-holes on a daily basis. (By the way, if anyone is offended by the implication that you’d ever urinate in an alley or between two buildings, please discontinue reading now. I make no guarantee your head won’t explode when I start mocking those who feel a moral playing field has been leveled, now that anti-pigeon science is being used on humans.)

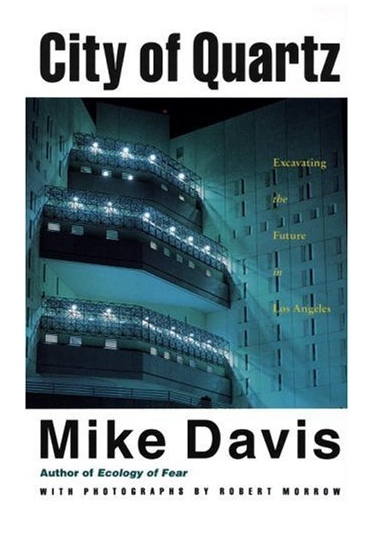

The fact is, residential management companies and corporate re-developers are exploring increasingly inventive tactics for shooing the poor elsewhere. It’s something I’ve seen all my life, and it wasn’t until the 1990 publication of Mike Davis’s fascinating (if bleak) City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles that I knew what to call it. Finally, there was a name for public parks and spaces that, by their very design, discriminated between the welcome and the unwelcome, the haves and have-nots: “Fortress L.A.”

The fact is, residential management companies and corporate re-developers are exploring increasingly inventive tactics for shooing the poor elsewhere. It’s something I’ve seen all my life, and it wasn’t until the 1990 publication of Mike Davis’s fascinating (if bleak) City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles that I knew what to call it. Finally, there was a name for public parks and spaces that, by their very design, discriminated between the welcome and the unwelcome, the haves and have-nots: “Fortress L.A.”

In the chapter, “Fortress Los Angeles: The Militarization of Urban Space,” Davis argues that architects in L.A. have led the way in “privatizing public space” through urban design intended to steer the unsightly out of places like Century City, Beverly Hills, and so forth. Though fairly self righteously written, a handful of friends and I devoured City of Quartz, quoting from it like a favorite movie (my term, MAN-EATERS, was born out of one such discussion). And while Davis’s views can arguably be taken as bloated Marxism, there’s no getting around his prescience in viewing prison construction as a de facto urban renewal program, predicting ICE micro-prisons and “designer prisons,” and believing the War on Drugs would double our prison population in one generation. Boy, was he right!

There’s also no getting around the fact that “bathrooms are for customers only” has become part and parcel of our urban world, something Davis calls “spatial apartheid.” Published 10 years before cell phone culture kicked off, City of Quartz foresaw a “universal electronic tagging of property and people.” And finally, on the subject of crowds, Davis wrote:

There’s also no getting around the fact that “bathrooms are for customers only” has become part and parcel of our urban world, something Davis calls “spatial apartheid.” Published 10 years before cell phone culture kicked off, City of Quartz foresaw a “universal electronic tagging of property and people.” And finally, on the subject of crowds, Davis wrote:

“…the designers of malls and pseudo-public space attack the crowd by homogenizing it. They set up architectural and semiotic barriers to filter out ‘undesirables’. They enclose the mass that remains, directing its circulation with behaviorist ferocity. It is lured by visual stimuli of all kinds, dulled by musak, sometimes even scented by invisible aromatizers.”

So…yeah: much of what the guy wrote was prophetic. Installing rows of steel spikes in the doorways of luxury apartment buildings fits today’s classist climate to the letter, from the missing Metro line between East LA and the beach, to Pacific Coast Highway homeowners disguising public ocean access as private property. (The really obnoxious ones issue parking tickets and hire goons to chase off visitors, and now, to counteract them — drumroll — there’s an app for that!)

So…yeah: much of what the guy wrote was prophetic. Installing rows of steel spikes in the doorways of luxury apartment buildings fits today’s classist climate to the letter, from the missing Metro line between East LA and the beach, to Pacific Coast Highway homeowners disguising public ocean access as private property. (The really obnoxious ones issue parking tickets and hire goons to chase off visitors, and now, to counteract them — drumroll — there’s an app for that!)

The ideas laid out in City of Quartz were today’s public mindset in the making. The extremity of the doorway spikes photographed in the UK may still be an ocean away, but gated communities disguised as Main Street, USA are their forbearers (fiction or no, see also T.C. Boyle’s Tortilla Curtain).

The ideas laid out in City of Quartz were today’s public mindset in the making. The extremity of the doorway spikes photographed in the UK may still be an ocean away, but gated communities disguised as Main Street, USA are their forbearers (fiction or no, see also T.C. Boyle’s Tortilla Curtain).

This brings me back to the NIMBY contradiction. Exclusionary and defensive architecture does have its purpose, such as when you’re pushing a baby stroller past someone smoking crack in the recess of a building near where you live. Yet for every crack smoker, urinator, puker, and people-of-Walmart who contaminate our privileged lives 14 seconds at a time, it helps to remember that 1.6 million children are homeless in America. In other words, delusional homeless people picking a fight with a cardboard box aren’t the only ones looking for hidden corners on hot days and cold nights. And isn’t it a tad hypocritical to coax your little Joey into giving away his used toys so other kids can play with them when you live behind “reminder spikes” installed by your home owners’ association to make sure none of those less fortunate children try to share his space?

Wouldn’t that technically be an excuse for solidifying a class ideal in the mind of someone with his whole world and life ahead of him? Do we really want the next generation to grow up thinking it’s ok to punish the poor? If that sounds like an exaggeration, just what level of rational analysis do you think a hungry nine-year-old is capable of? Never mind the ‘ol wino talking to himself as you take out your trash, we need to think of the young ones from both a moral and a practical standpoint. I mean, do we really want to harden the hearts and minds of an ever growing population of homeless children?

If spatial apartheid exists, and I believe it does, it means the endgame is to keep us separated into controlled and monitored groups. What end result can we expect, then, beyond the neo-militarization of our world? And for that, there’s simply no excuse.