“What’s in a name?” isn’t a trick question.

It’s a dumpster for opinions.

Before Andrew Cuomo walked out the door, the 56th Governor of New York signed Senate Bill S3332, amending the language of New York state law to replace all instances of the words “inmate” or “inmates” with the words “incarcerated individual” or “incarcerated individuals.”

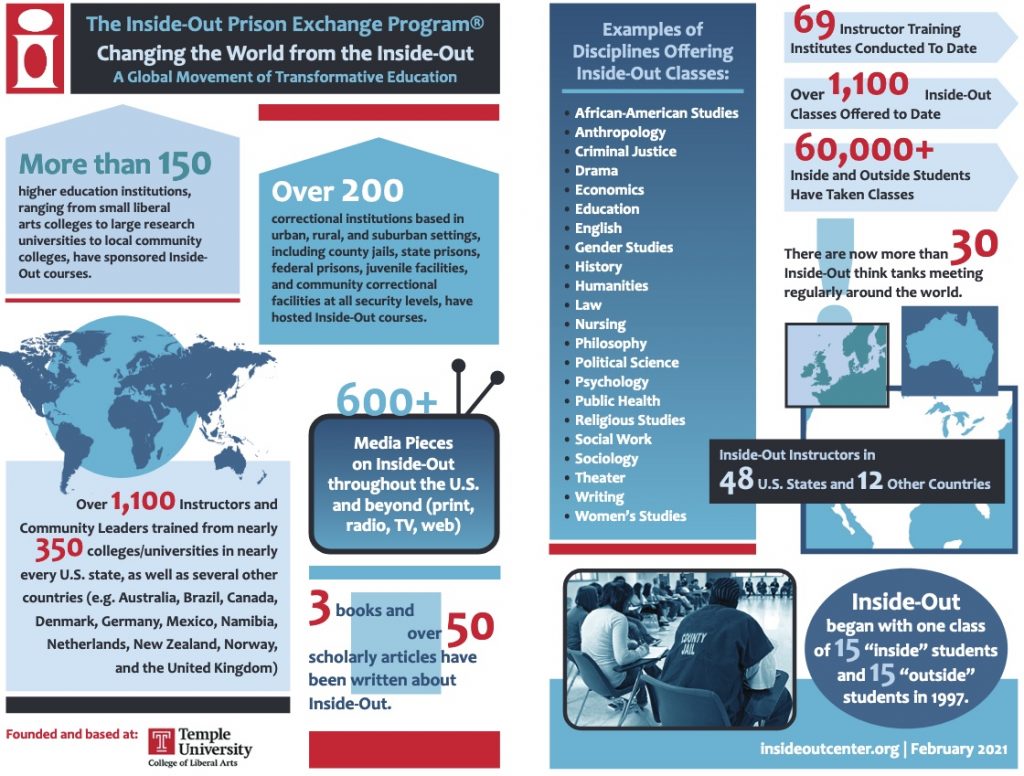

Our national dialog on the power of names, be they for sports teams or co-worker pronouns, gave rise to SB S3332 and its approval. To those who wonder what purpose the bill might serve, the idea is to leave no stone unturned in seeking ways to lift negative reinforcement, terminology, and training. And considering how indelibly the American public has been trained to recognize those behind bars, it’s no surprise that some are crying, “Them too? What, they’re guests now?”

As if the premise of recognizing humanity wouldn’t include people who have broken the law.

But yes, widening the front lines of the identity war to include the incarcerated is already goading some into throwing up their hands. “New York lawmakers must have tortillas for brains,” whistles a Law Enforcement Today editorial, “because that’s the only way someone could wrap their mind around this legislation and think it actually is going to somehow make attaining gainful employment and housing easier after someone is released from prison.” The piece goes on to call the legislation dumb and pointless.

Which it might be, if SB S3332’s aim was to make those things easier. Instead it’s an attempt––finally––to limit the countless ways in which we make it unnecessarily harder to prevent recidivism and promote post-incarceration success. The same dismissive article also quotes the text of the bill:

“Studies have shown these terminologies have an inadvertent and adverse impact on individuals’ employment, housing and other communal opportunities. This can impact one’s transition from incarceration, potential for recidivism, and societal perception. As a result, this bill seeks to correct outdated terminology used to refer to incarcerated individuals.”

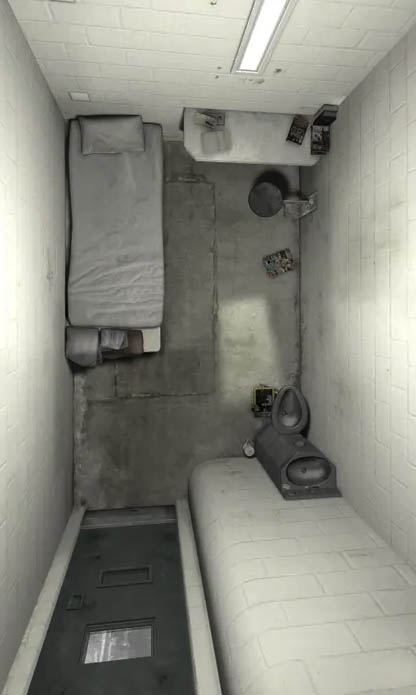

Since humanitarian acknowledgement isn’t revoked at sentencing, what’s so objectionable about putting it on paper? When you live in a concrete box, simple gestures are magnified. Encouraging offenders to see their bottom as a bounce is a matter of life-and-death. It’s something that starts with correction’s leadership and lives in the very paperwork of confinement.

Imagine living inside a Department of Motor Vehicles, say, one that’s located inside of a parking structure. If you can picture this, you have a good grasp of what it’s like to live in prison. Forget about having a visitor or buying Chapstick without the right authorization: white, blue or canary. And 20 to 40 times a day, you identify yourself using only your last name and inmate number, a number technically assigned to a case file, not a person. But nobody knows the difference after a while. We’ve gotten used to thinking of inmates as numbers, and the narrowness of this thinking is reinforced with every “Inmate, wait here!” and “Inmate, where’s your permission slip?”

“If you can’t do the time…” yeah-yeah-yeah.

This continual degradation or any of the other downsides to human warehousing is not actually a part of the punishment to which one is sentenced in a courtroom. One is sentenced to a period of confinement and/or time during which one is disqualified from fully participating in society. Everything else––including the dehumanization that we enable by allowing it to persist beyond the perimeter walls––is “bonus justice.” I’ve written about that before here and here, and it’s just as true for names as it is for actions.

What do we civilians know about the soul grinding effects of this genericized use of “inmate,” “felon,” and “convict,” be these “names” spoken or documented in court transcripts, work assignment evaluations, or in the language of social services law, county and general municipal law, civil rights, election, and labor law? It’s long past time we end this bonus justice.

Personally, I favor “adult offender,” because one can stop offending, whereas one can’t stop inmating or feloning. It can be damaging to conflate one’s actions with who they are, and downright damming to assign that misnomer linguistic permanence.

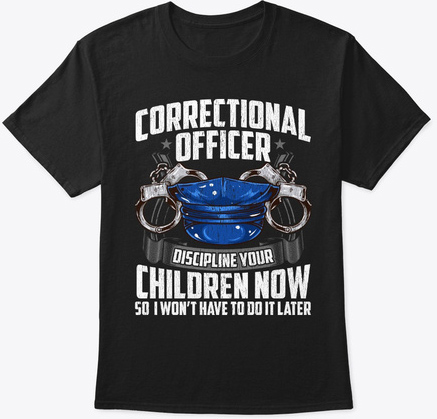

Yet some folks still can’t or won’t see past a name. There will be those who hear about the NY legislation and insist, “They did something wrong: No special treatment for inmates!” These taxpaying geniuses couldn’t care less about how a reduction in denigrating terminology can serve the ultimate goal of redirecting offenders rather than simply recycling them. But if they don’t care what certain names can do to a person, could they grasp what their continued use will do?

Because:

-They will reduce self-direction, until “follow the yellow line to the showers” becomes the only way to live.

-They will reduce self-image to the point where scoring oneself a roll of toilet paper (or a fix) = a good day.

-They will reduce self-esteem in such a way that it can only be regenerated via prison codes and philosophy.

-They will reduce a need for self-expression and replace it with a need to enforce.

The question is, then, are we so unwilling to let go of our preconceived ideas of what others “deserve” that we’re ok with such a cost?

“I confused things with their names: that is belief.”

––Jean-Paul Sartre, The Words

.