You’d think someone would have covered what it was like to experience the LA riots behind bars in the past 25 years. Something. Anything. But nope.

Then again, with Netflix’s Orange is the New Black ranking just below LA LA Land in grounded reality, such coverage probably would have been twisted into the taffy of a Broadway musical anyway.

So while a mention would’ve been interesting, I have my own view…

Wasco State Prison opened in February, 1991. With California’s severe overcrowding problem, the facility was filled faster than inmate classification procedures could keep up. (The prison was “populated” before construction was complete.)

Wasco State Prison opened in February, 1991. With California’s severe overcrowding problem, the facility was filled faster than inmate classification procedures could keep up. (The prison was “populated” before construction was complete.)

Having been the 75th inmate to in-process, I can tell you it was already preposterously bloody: verbalizations of assaults and stabbings began on the busses. And they weren’t over pride and payback –this was about all that virgin prison yard territory.

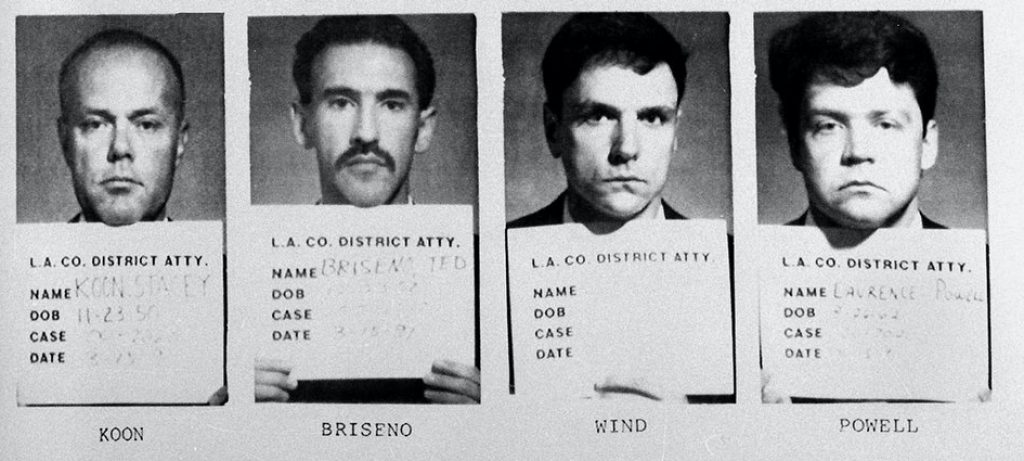

Thirty days later, in early March, the “outside world” learned the name Rodney King. So, too, did the inmates of Wasco. When local KTLA 5 began airing George Holiday’s video footage of King’s beating at the hands of the LAPD, the facility was placed on an immediate lockdown, which lasted for four days.

Thirty days later, in early March, the “outside world” learned the name Rodney King. So, too, did the inmates of Wasco. When local KTLA 5 began airing George Holiday’s video footage of King’s beating at the hands of the LAPD, the facility was placed on an immediate lockdown, which lasted for four days.

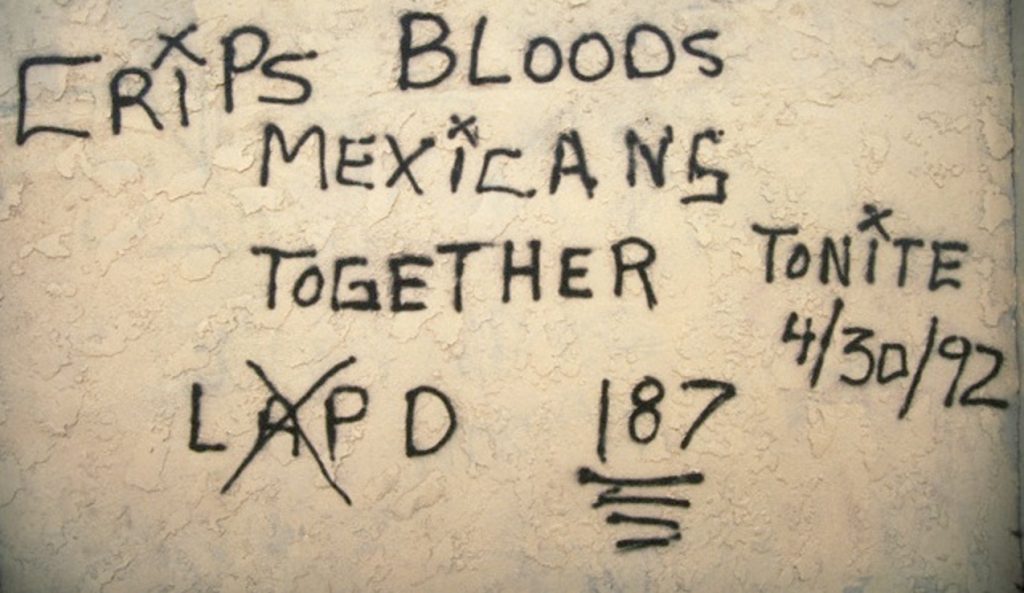

Talk of law enforcement inequality –constant penitentiary chatter in its own right– became louder and angrier. As in the rest of the world, there was no escaping growing resentment as Holiday’s camcorder footage became a national dialog. But our world was crammed into what’s basically a parking structure with electric fences. Not much room for growth there.

And the staff had it tough as it was, ridding the Yard of its territorial influences and flat out murderers. California’s corrections higher-ups made their jobs harder, too, determined as they were to flaunt the newfound bed space, ready or not. Visible tours of suits and politicians back then were frequent, so the increase in racial tension following the King beating couldn’t have come at a worse time.

And the staff had it tough as it was, ridding the Yard of its territorial influences and flat out murderers. California’s corrections higher-ups made their jobs harder, too, determined as they were to flaunt the newfound bed space, ready or not. Visible tours of suits and politicians back then were frequent, so the increase in racial tension following the King beating couldn’t have come at a worse time.

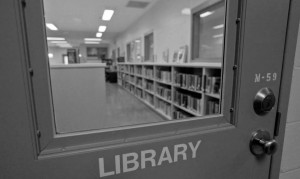

I’d managed to finagle myself relative sanctuary during that first year by serving as a library clerk, and then as an aid for a civilian teacher in the education building. When a lockdown occurred, that teacher would often request that I be issued a pass and escorted to his classroom. Badges patrolled the education building constantly, but none cared if we graded papers while watching movies on VHS.

During that year, the teacher and I filled a large bulletin board with newspaper clippings related to the King investigation and trial. I was lucky to participate in many conversations and learn from the perspectives of men who inhabited a South Central world under the boots of inequality, led by LAPD Chief Daryl F. Gates (aka “Chief Chokehold“).

During that year, the teacher and I filled a large bulletin board with newspaper clippings related to the King investigation and trial. I was lucky to participate in many conversations and learn from the perspectives of men who inhabited a South Central world under the boots of inequality, led by LAPD Chief Daryl F. Gates (aka “Chief Chokehold“).

Twenty-five years ago this month, the warden’s office didn’t have any more of a clue than we did when the King verdict would be announced, but the guy was smart enough to have everyone in their cells when it came down. On April 29 at 3-something in the afternoon, those who’d purchased mail-order televisions started screaming. For the next seven straight hours, inmates of all ethnicities either cheered angrily for the verdict or railed angrily against it. It was as black ‘n white as anything I’d ever encountered.

In anticipation of hand-to-hand genocide, the number of Badges was tripled in each unit. Crisis Response Goons stood around in their tactical finery, looking like warnings against steroid abuse. We were fed in our cells. I found I couldn’t talk my way into a work pass if blood had been streaming from the center of my palms.

So we stayed in our cages and saw Los Angeles burn. We watched Reginald Denny’s head get cracked open by that cinder block, followed by Chief Chokehold’s announcement that he’d bring it all under control in one night. We saw everything that you did, except behind bars meant being enveloped by what sounded like horses frightened by fire, thrashing violently, desperate to stampede.

So we stayed in our cages and saw Los Angeles burn. We watched Reginald Denny’s head get cracked open by that cinder block, followed by Chief Chokehold’s announcement that he’d bring it all under control in one night. We saw everything that you did, except behind bars meant being enveloped by what sounded like horses frightened by fire, thrashing violently, desperate to stampede.

I listened carefully at my cell door as inmates from South Central relayed news copter play-by-play to those without TVs. As they shouted the locations of rioters and looters in relation to their own ‘hoods and homes, I compared what I was hearing to what I saw on my own tiny black ‘n white screen. For five full days, the men around me went to work at the front of their cells, yelling and pounding and punching in a relentless and deafening cacophony. The guards’ use of the PA system alone was its own psychotic, 80 decibel soundtrack to KTLA’s footage. I began separating squares of toilet paper from my roll, softening ‘em up with saliva, and stuffing ‘em into my ears. Every time I caught a glimpse of myself in the polished steel “mirror” it looked like rabbit ears were jutting from my head.

I listened carefully at my cell door as inmates from South Central relayed news copter play-by-play to those without TVs. As they shouted the locations of rioters and looters in relation to their own ‘hoods and homes, I compared what I was hearing to what I saw on my own tiny black ‘n white screen. For five full days, the men around me went to work at the front of their cells, yelling and pounding and punching in a relentless and deafening cacophony. The guards’ use of the PA system alone was its own psychotic, 80 decibel soundtrack to KTLA’s footage. I began separating squares of toilet paper from my roll, softening ‘em up with saliva, and stuffing ‘em into my ears. Every time I caught a glimpse of myself in the polished steel “mirror” it looked like rabbit ears were jutting from my head.

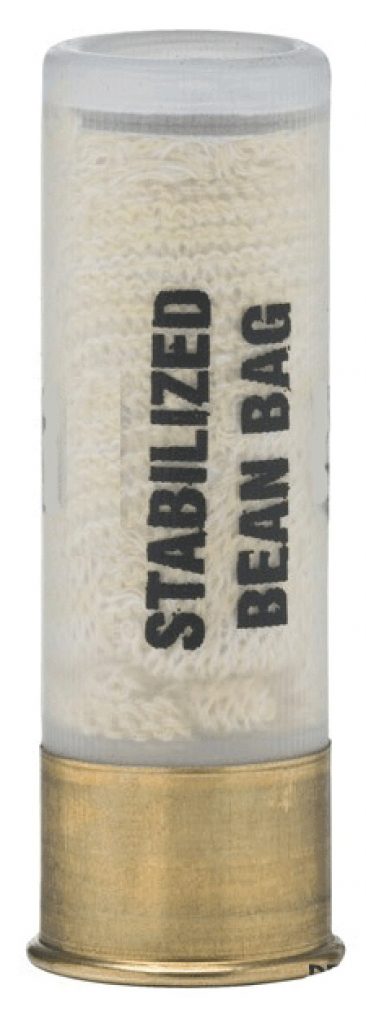

We heard that in housing Unit 2, inmates were being released one by one for solo trips to the showers: in fact, those assholes had been allowed to shower from day three. Then some idiot used his time to turn a mop into a lance and charge the communal television, screaming at the cops back at home. He broke the screen after four solid hits before the Control Booth Badges nailed him with bean bag rounds. As he ran around the otherwise empty common areas, cursing, he was cheered on. Thanks to him, our unit wasn’t approved for single shower rotation ’til day seven.

We heard that in housing Unit 2, inmates were being released one by one for solo trips to the showers: in fact, those assholes had been allowed to shower from day three. Then some idiot used his time to turn a mop into a lance and charge the communal television, screaming at the cops back at home. He broke the screen after four solid hits before the Control Booth Badges nailed him with bean bag rounds. As he ran around the otherwise empty common areas, cursing, he was cheered on. Thanks to him, our unit wasn’t approved for single shower rotation ’til day seven.

Medication was brought to our cells like in every other lockdown, except that none of the caucasian Kern County civilian medical employees would come to work, which meant there was a serious shortage of licensed staff to distribute prescriptions. “So you Charlie-white cops rule the hospital department too, huh!?” said my “neighbor” every time his blood pressure medication was dispensed by an unauthorized Badge.

On television, there were the fires, beatings and pride with which hate had been weaponized…

All of it was straight out of the prison exploitation flicks of the 1970s, a real Roger Corman fever dream in which the Koreans almost steal the show. (Three months later, in fact, I’d be sharing a cell with a Korean-American my age who used the chaos to burglarize the stores his own family and friends were trying to protect. Not TVs, though: cash, from illegal card games held in those very shops.)

Front-line Badges faced their own MIA personnel issues, and it would take the crybaby guards who called in sick more than a year to live it down. During that year, there was no escaping speculative whispers of “chickenshit” among guards and inmates alike (because “we’re all in here together“ does indeed seep into the day-to-day grind).

Twenty-seven days after the riots began, we’d been so thoroughly marinated in seclusion and lack of fresh air that we were deemed unlikely to “jump off” over what had by then become old news. The warden’s office was right again; they let us out and there was relative peace.

I live today, happy to have been there, and paying attention.

I offer no in-depth analysis of the riots, Rodney King, or what the ensuing 25 years means culturally or politically. I find I’m still just as cynical as I was back then. “How far we’ve come” isn’t as socio-culturally rosy as some would have us believe – period.

But we can stay aware of how our actions affect those around us. Looking back, I don’t think I can recall a time when how we treat others has been more important than it is today. That’s where the good dialog lives – in that one little hard to reach spot where we only look to see if our side of the street is clean.

Be sure ‘n check out director Sacha Jenkins’ fist-in-the-air examination of the Los Angeles Police Department’s relationship with African-Americans via his Showtime documentary Burn Motherfucker, Burn!

.