I know life in a prison classroom, and the learning environment you may or may not find once you’ve taken a seat.

I know life in a prison classroom, and the learning environment you may or may not find once you’ve taken a seat.

A brief click-through of “5 Projects to Watch in 2016” from Correctional News leaves me wondering how much prison officials really know about the obstacles inmates face just getting through a detention facility’s classroom door. What does it matter, you ask? Well, in an era where words like “reform,” “rehabilitation,” and “recidivism” are on everyone’s lips, it’s important to know when a component as critical as education is simply being given lip service.

Correctional News covers prison operations, design, and construction. It celebrates grand openings and groundbreakings because imminent completion dates tend to matter to rubber mattress merchants, vendors of detection products, and shower flooring suppliers.

Currently showcased are the East County Detention Center near Palm Springs, for example, which is set to open in 2017, the Kern County justice facility in Bakersfield, and the new Utah State Prison, among others. California being where I paid my debt to society, I tend to monitor its prison system more closely than I do others. But all of these entries have something in common, and that’s my point: they feature anemic descriptions of the education facilities also under construction. Rehabilitation-as-footnote here, will eventually make corrections administrators and state officials look as though they’re simply hanging wreaths of rehabilitation on freshly painted classroom doors and leaving it at that.

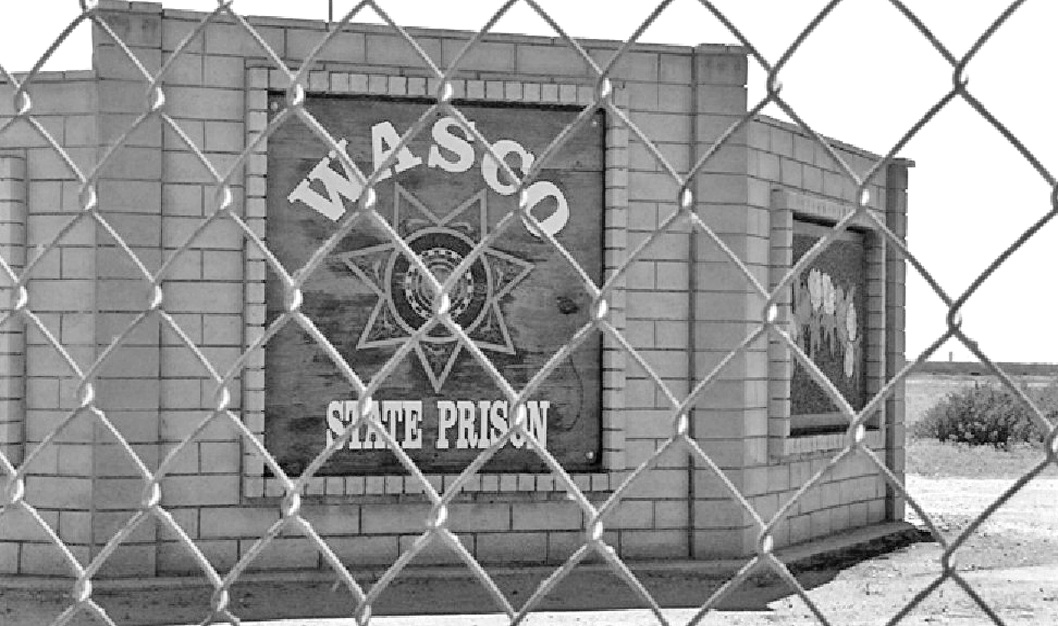

After Wasco State Prison’s grand opening, I spent 18-months as a teacher’s assistant in its new “education building.” The instructor for whom I clerked was told to come up with a pre-release curriculum that would prepare soon-to-parole inmates for apartment rentals, job applications, check writing, filling out California driver’s license forms, and so forth. No help, no direction, just: “Here’s a blackboard and some chalk: now go teach.” In other words, “You figure out all this rehab stuff so we can focus on the electrical output of the perimeter fences.” (Lucky for me, he was brilliant despite these obstacles.)

After Wasco State Prison’s grand opening, I spent 18-months as a teacher’s assistant in its new “education building.” The instructor for whom I clerked was told to come up with a pre-release curriculum that would prepare soon-to-parole inmates for apartment rentals, job applications, check writing, filling out California driver’s license forms, and so forth. No help, no direction, just: “Here’s a blackboard and some chalk: now go teach.” In other words, “You figure out all this rehab stuff so we can focus on the electrical output of the perimeter fences.” (Lucky for me, he was brilliant despite these obstacles.)

Now, at a time when the public and policymakers are presumably paying a lot more attention to the issues that communities and inmates face upon their release, it’s surprising how recognizable that dismissive vibe still is. In the face of renewed interest in what may actually work to reduce recidivism (life and job training, parenting classes, and programs that teach parolees how to live), inmate education innovation is still challenged by tokenism. In California, at least, it really makes the “R” in “CDCR” feel tacked on.

Behind those aforementioned perimeter fences, newly minted facilities may house pristine prison classrooms, but there’s still far too little attention paid to what goes on in them. Unsupported faculty still stand at blackboards (or maybe dry erase boards), at the mercy of day-to-day operations just as inmates are at the mercy of guards to give them access (and no, Yard bullies aren’t the only ones who charge “rent” just because they can).

It’s easy to blame outdated prison facilities for a lack of success: there’s fodder galore throughout the country, and it reads well in the media. But brand new desks and chairs are no guarantee of attendance or results. I don’t blame prison wardens and other facility administrators for this directly, and I didn’t even while I was at Wasco. They’re not (typically) evil people out to secure their jobs or avoid the guard union’s wrath. Security will always be priority number one for these folks, and it should be. I’m simply suggesting there should be a number two.

Yes, back at Wasco, teachers and other civilian employees were thoroughly screened – but as security risks, not for their academic character.

Yes, back at Wasco, teachers and other civilian employees were thoroughly screened – but as security risks, not for their academic character.

In fact, I doubt their interviews were as extensively designed as the inmate classification process. (Sacramento was desperate for bed space and opened the facility an arguable two months too soon, allowing territory-claiming troublemakers and high-level shot-callers to breach the inaugural A-yard. That first batch of teachers was either extremely misled, or brave, or both.)

And since I owe my own subsequent success directly to the lengths a civilian prison educator will go to in order to set a good example –despite preoccupied, inadequate leadership– I do want to see more comprehensive measures in place. Moreover, what assurances do we, as taxpayers, have that steps are actually being taken to ensure prison classrooms are offering the sorts of effective learning strategies we’re paying for?

And this brings me back to Correctional News. If educational and vocational training facilities aren’t described more purposefully to builders, vendors, and administrators, how can we expect them to support an emphasis on genuine rehabilitation? I mean, congratulations to the soon-to-open facility with 105,000 square feet of glass walls, but learning environments are special too. Education wings should be described like the V8 engines we (ostensibly) want them to be, not as the chromed plastic trim surrounding our modern day rear bumpers. Are they being built and equipped for performance, or simply to look good?

Because that matters. From construction to action, when it comes to redirecting offenders rather than just recycling them, what messages are we sending? We know that boots, bars, and badasses will always come first, but do those working in penitentiary education buildings feel like islands left to fend for themselves? How do we encourage our teachers to measure success by inmate progress and parolee preparedness rather than simply by compliance? How do we, from the general public to prison administrators, set expectations – and provide appropriate environments to support those expectations – that allow educators to distinguish themselves from any other baton-wielding goons?

Because that matters. From construction to action, when it comes to redirecting offenders rather than just recycling them, what messages are we sending? We know that boots, bars, and badasses will always come first, but do those working in penitentiary education buildings feel like islands left to fend for themselves? How do we encourage our teachers to measure success by inmate progress and parolee preparedness rather than simply by compliance? How do we, from the general public to prison administrators, set expectations – and provide appropriate environments to support those expectations – that allow educators to distinguish themselves from any other baton-wielding goons?

I’m not suggesting we forget that prison teachers walk a fine line between requiring obedience and encouraging the abandonment of old behaviors: I’m simply saying it can be done, especially if we start at the beginning. Corrections industry professionals researching which bids are being awarded to which architectural firms, joint-venture executives, and contractors need to know about more than just expansion possibilities for companies who sell steel beds, video visitation booths, and razor wire. I say it starts with builders; it starts with designing the true intended purpose of “corrections and rehabilitation” facilities into the walls themselves. They may still be made of concrete, but what speaks louder or carries more messages to inmates than the walls of a prison corridor?

Looking at these “5 Projects to Watch,” I remember how long Wasco’s classrooms sat empty. In the first year, custody brass and administrators were pulling their hair out trying to get the place to run right, but by the end of the second year the joint was so packed with bodies that education building desks were replaced with three-tiered bunks. Certainly the space was (eventually) re-converted to classrooms, but think of all the individual opportunities for growth and personal change that were lost when the Whack-A-Mole of impromptu bed space took over. Had there been better planning for and a stronger commitment to such things from the start, this might have been avoided.

Looking at these “5 Projects to Watch,” I remember how long Wasco’s classrooms sat empty. In the first year, custody brass and administrators were pulling their hair out trying to get the place to run right, but by the end of the second year the joint was so packed with bodies that education building desks were replaced with three-tiered bunks. Certainly the space was (eventually) re-converted to classrooms, but think of all the individual opportunities for growth and personal change that were lost when the Whack-A-Mole of impromptu bed space took over. Had there been better planning for and a stronger commitment to such things from the start, this might have been avoided.

In sum, there’s a lot of talk these days – in addition to good intentions and expanded education policies, reentry programs, and reform proposals – but real change starts at the top, and it starts at  the beginning. It starts with corrections officials making deliberate design and building choices vis a vis inmate rehabilitation, recruiting committed and qualified education professionals, and ensuring that the sense of urgency for genuinely reforming inmates and preparing them for successful reentry trickles down to associate wardens, sergeants, and lieutenants.

the beginning. It starts with corrections officials making deliberate design and building choices vis a vis inmate rehabilitation, recruiting committed and qualified education professionals, and ensuring that the sense of urgency for genuinely reforming inmates and preparing them for successful reentry trickles down to associate wardens, sergeants, and lieutenants.

Yes, keeping things calm and safe for guards, civilian employees, and even inmates is critical. But so is stepping out of the blinder-guided “jailer” role long enough for the roots of education to take hold. True anti-recidivism depends on it.

And if that doesn’t work? Then hard-boiled union officials, administrators, and prison guards need to recognize that those calling (and paying) for prison reform have won the big arm wrestling match for the time being. So unlock the doors, will ‘ya?

.