Walking in each other’s shoes is not about how you would feel dealing with their circumstances. It’s about seeing how the other person feels dealing with their own circumstances.

Inmates and guards betray their respective roles more often than one might imagine, and more often than custody comportment will allow either to admit.

In fact, even aside from 12-step support stuff, so-called emotional safes zones do exist on maximum security prison yards. They feel as odd as they are accidental, and God help the fool who utters a phrase like “emotional safe zone” out loud.

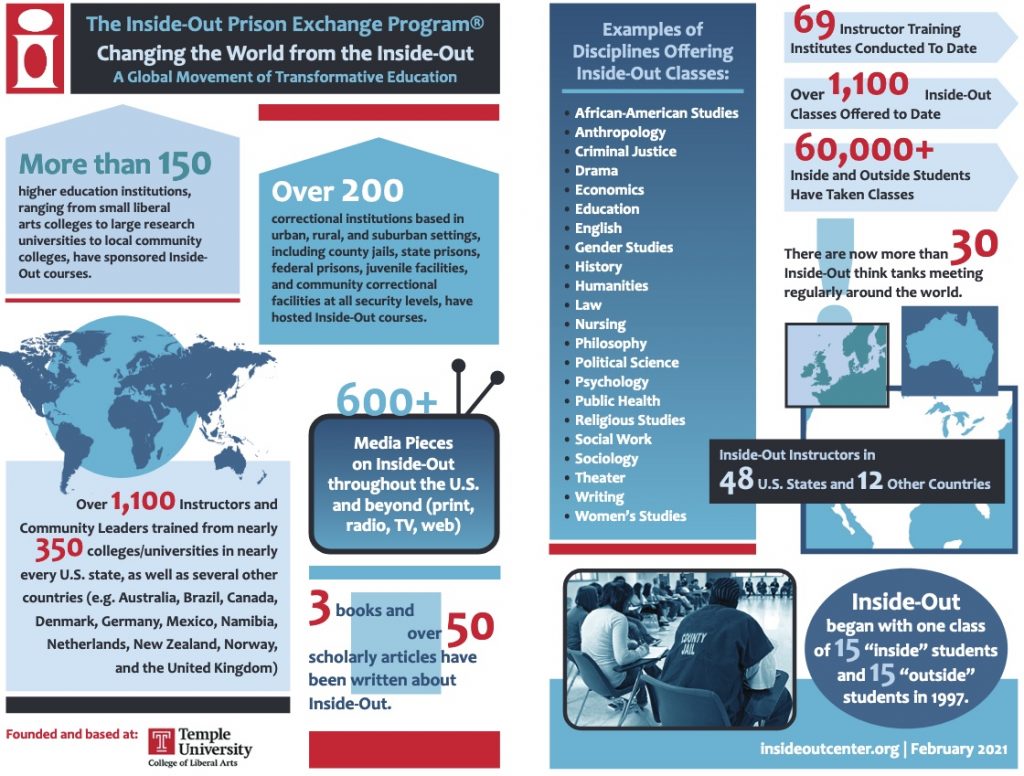

Capitalizing on this all too human need to be heard and understood is a program modeled on the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, which places college students in classrooms with inmates for semester-long, full-credit courses. Today more than 150 institutions of higher education have successfully sponsored courses in more than 200 correctional institutions. Even more notable, since 2016, Police Training Inside-Out (PTI-O) has been explored as a way to better train cops.

A partnership between Duquesne University (and founder Norman Conti), the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, and the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, PTI-O was designed to bring cadets and cons together once a week in an academic seminar held behind prison walls. The idea was to supplement traditional police academy training with a way for law enforcement officers to develop a more nuanced professional vision than “us versus them.” Based on the depth of the interaction, a similar mindset shift is expected to occur among participating inmates as well.

During my own incarceration, one particular Corrections Officer worked our unit’s lonely “lights out shift” quite frequently. He was a schlub who basically listened to the fellas snore, pray, and turn the pages of books. The warning about him went, “Pretend you’re asleep when Officer X does his rounds: that dude’ll talk your ear off.”

Guys shuffling to and from the toilets during the night would report his conversations with various inmates, but it was less a matter of, “What’s that rat-snitch blabbing to the badge about?” and more, “Ha! That dummy forgot to tip-toe!” I was that dummy once or twice myself. Returning from the can, I’d been waved over to his desk, only to endure mindless blather about his crappy vacation or doc-ordered dietary changes.

And this guy wasn’t alone. I encountered or heard about several prison guards who took psychic hostages this way, though most of us were at least begrudgingly charitable. They’d roll their eyes when we talked about our big post-custody plans, and we’d roll our eyes when they trotted out the obligatory (though likely part-true): “Believe me: I could just as well have wound up in your shoes.” Never mind the similarities of our breathing the same prison air, burying much of the same PTSD, or the burdens of secrets and stereotypes.

There was relief and humanity found in such truces, and I know many of the men on both sides of those exchanges felt it. Sometimes those fleeting moments –mundane as they may have been– were even slightly charming. But the very best were the exchanges in which we got into each other’s heads just a little, and then disclosed our findings.

For a few days I repeatedly dropped, “The sergeant with the missing finger told me how he lost it!” I hadn’t been the only person he told, but for a minute I proudly thought otherwise.

A typical PTI-O class puts police and inmates in small groups, discussing questions like: “What are prisons for?”; “Why do people commit crimes?”; “What are some things that prisons do well/poorly?”; and “What would you say to the assertion that prisons are now our country’s principal government program for the poor?”

Conti, the program’s founder, says he still deals with reluctance on both sides. To get them to sign up, some inmates have to be reminded that it’s better for their communities back home to deal with a cop who knows how to do more than divide the world into “citizens” and “predators.”

On all fronts, the police training version of Inside-Out represents cutting edge criminal justice reform and offers a true hand in reversing mass incarceration. It validates a small but valuable prison souvenir/takeaway of my own: “Sometimes you have to get in the box to think outside of it.”

Check out Officer Training Behind Prison Walls to learn more about how the program works. Maybe bring it up to cop you know and see if they roll their eyes.

.

.