How a story makes us feel should not be the measure of its historical worth.

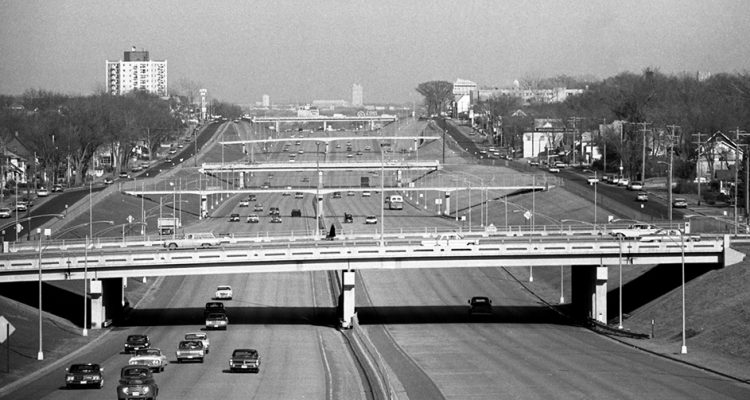

America’s Interstate Highway System, constructed from the 1950’s through the 1970s, saw massive multi-lane middle fingers run through poor neighborhoods and communities of color. These were districts lacking tourism, valuable land, and political power. In many instances, like in Oak Park, Alabama, they had targets on their backs.

Obliterated in the late 1950s to make way for Interstate 94, Rondo was the backbone of the Black community in St. Paul, Minnesota. By the time I-94 opened in ’68, Rondo had lost “homes, churches, schools, neighbors, and valued social contracts.” With 15% of its population displaced, 300-400 Black-owned homes destroyed, and the loss of its chapter of the NAACP, Rondo would never see its diverse and thriving trajectory fulfilled as it might have.

Alabama’s Highway Director Sam Engelhardt, whose State Senate campaign cards read, “I STAND FOR WHITE SUPREMACY SEGREGATION,” ensured that Interstate 85 would wipe Oak Park, a neighborhood of Black civil rights leaders and its active voters, right off the map.

In other states, transportation infrastructure indiscriminately zigzags where it could have continued along a straight path, flattening Black neighborhoods despite the availability of alternate routes. So went the golden age of American road building.

Yet today, “Remember Rondo!” hardly has the same ring of social acceptance as other historical reminiscences about harm caused, like “Remember Pearl Harbor” or even “Remember the Alamo.”

And why should Remember Rondo —despite its grounding in historical fact—be considered by so many these days to be anti-American blasphemy? Does its viability make you hate America, as The Heritage Foundation, Turning Point Academy, and GOP Senator Ted Cruz all insist it will? Is it really an “attack on white people,” such that teaching history of this sort is, in the words of radio talk show host Michael Savage, “exactly what was done to the Jews in Germany in the 1930s…the road to the death camps”?

Yikes! Here I thought it might inspire someone to help protect us from future historical offenses.

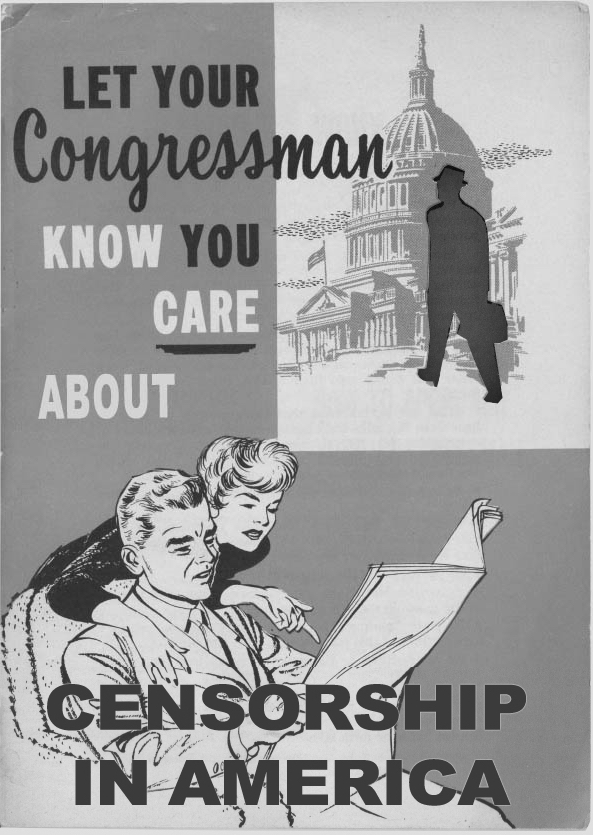

Critical Race Theory and culturally responsive education aren’t the same, but they are under attack by those intent on misrepresenting them. And enemies of either would have you reject unheard voices and believe that racial equity is anti-American. It’s not.

Cruz’s recent claim that Critical Race Theory, originally conceived as a framework for understanding the relationship between race and American law*, “is every bit as racist as the Klansmen in white sheets,” is idiotic. Lawyer Cruz well knows this. In its broader conception (also never shamefully hidden behind white robes) CRT provides a path to addressing the inequalities that are historically embedded in our political, social, economic systems—because only by acknowledging them can we work to change them.

Former economics professor Michael Harriot puts it this way: “A complete understanding of economics includes the laws of supply and demand, why certain metals are considered ‘precious,’ or why paper money has value. But we can’t do that without critically interrogating who made these constructs and who benefited from them.” And he’s not even talking about changing those constructs. Neither, for that matter, is enlightening students about the literally structural racism found in the Interstate Highway System a) a statement about individual racism or b) necessarily a demand for change. It’s really just an acknowledgement of a more complete historical truth.

But for the record, it’s highly unlikely that Critical Race Theory is being taught to your precious child: it’s rarely even taught to undergraduates for all its complexity. What is hopefully part of junior’s upbringing is culturally responsive education, which is less a thing than an overdue recognition that kids learn best when they have ways to connect what they learn to their own lived experiences. Brown University calls culturally responsive education, which was conceived in 1994, BTW, “a pedagogy that acknowledges, responds to, and celebrates fundamental cultures [to] offer full, equitable access to education for students from all cultures.”

Equitable access is muy anti-Americano, no?

And again, neither Critical Race Theory nor culturally responsive education explicitly advocate for, for example, calling out a Texas Legislature that threatens to withhold state funding to state universities refusing to “Remember the Alamo” the ‘right’ way, though it turns out, according to a consensus of historians, that the 13-day siege wasn’t about the mean old Mexican army after all. The Texians defending the Alamo—alongside their Tejano brethren, who have since been written out of the story—were fighting to preserve the slavery they depended upon for their cotton trade. When the Mexican government told ‘em to pay up in taxes and/or free their slaves, the ranchers turned to a carpetbagging former congressmen, a Louisiana con artist and knife-welding crackpot named Jim Bowie, for help. And they were defeated handily by the army of General Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Despite this defeat, and despite the widespread theory that Davy Crockett might have actually surrendered before he was executed, Texas lore demands fealty to the false narrative of white heroes who single handedly took on those dirty Mexicans and fought valiantly to the death.

Now look, I know everyone and their mother omits things from and/or embellishes their favorite personal stories. But when it’s a matter of a historical record on which the future gets built and funds get allocated, it’s not okay for the “natural” or “patriotic” way of seeing things to minimize the contributions of one group while inflating and celebrating the contributions of another. And if you care about truth in history, you’ll want to correct that record. Do we really want a government that deliberately stands in the way of that?

Of course, not everyone is interested in complex truths, which both CRT and culturally responsive education enable. Us-versus-them is much easier of a narrative to create, promote, and consume. The worst part is that recent politics, fake news, and American social trends all demonstrate that truth itself is beside the point these days.

But once more, how a story makes us feel shouldn’t be the measure of its historical worth.

.

.

*Should you take issue with the contention that race and American law are intertwined, may I direct you to: Dred Scott v Sanford, Plessy v Ferguson, Brown v Board of Education, and many, many other cases illustrating the U.S. Supreme Court’s evolving thoughts on that very matter.

Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA Library.